Sermon for Transfiguration, Year B, February 11, 2024

This Wednesday is Valentine’s Day,

in addition to being Ash Wednesday.

It also happens to be the 18th anniversary

of my engagement to Pastor Jennifer.

As I have thought about this passage

from the Gospel of Mark,

I have been drawn back,

again and again,

to a day just weeks before Valentine’s Day.

Jennifer and I had spent the winter break apart.

We had been in touch,

by phone and text,

but in those days before Facetime and Zoom,

we had not seen each other.

We had gone into this break

on an uncertain note—

which I will freely admit

(and if I didn’t, Pastor Jennifer would tell you)

was my fault.

I could tell that she was far more certain

about the future of our relationship

than I was.

I didn’t what to lead her on

if this didn’t develop into something more on my end.

So, trying to do the right thing,

I told her about that uncertainty

and asked for a break.

Man, was I stupid.

When we finally met up again after winter break,

the second I saw her,

I understood why poets and artist

talk of sparks and fireworks.

In a split second,

I knew in my bones

that I was looking at my wife.

I made my amends,

and as love keeps no record of wrongs,

we picked up right were we left off.

But that moment

had changed how I saw Jennifer,

how I saw the rest of my life.

It changed how and what I dreamed

about the future.

It changed how I saw everything I had been through

up to this point.

Eighteen years,

one son,

5 degrees,

2 ordinations

and 8 zip codes later,

knowing what I know now,

not only would I still ask,

I would ask sooner.

So, what does any of that have to do

with Mark, Chapter 9?

Good question.

“Six days later,”

says the text.

Six days earlier,

Jesus asked his disciples who people say he is.

There were a lot of answers,

John the Baptizer back from the dead,

Elijah, or one of the prophets.

Jesus asks who they say he is,

and Peter makes his famous confession,

“You are the Christ!”

Jesus then predicts that he will be handed over,

killed,

and on the third day,

rise again.

Peter rebukes him,

and Jesus returns the rebuke.

Now,

six days later,

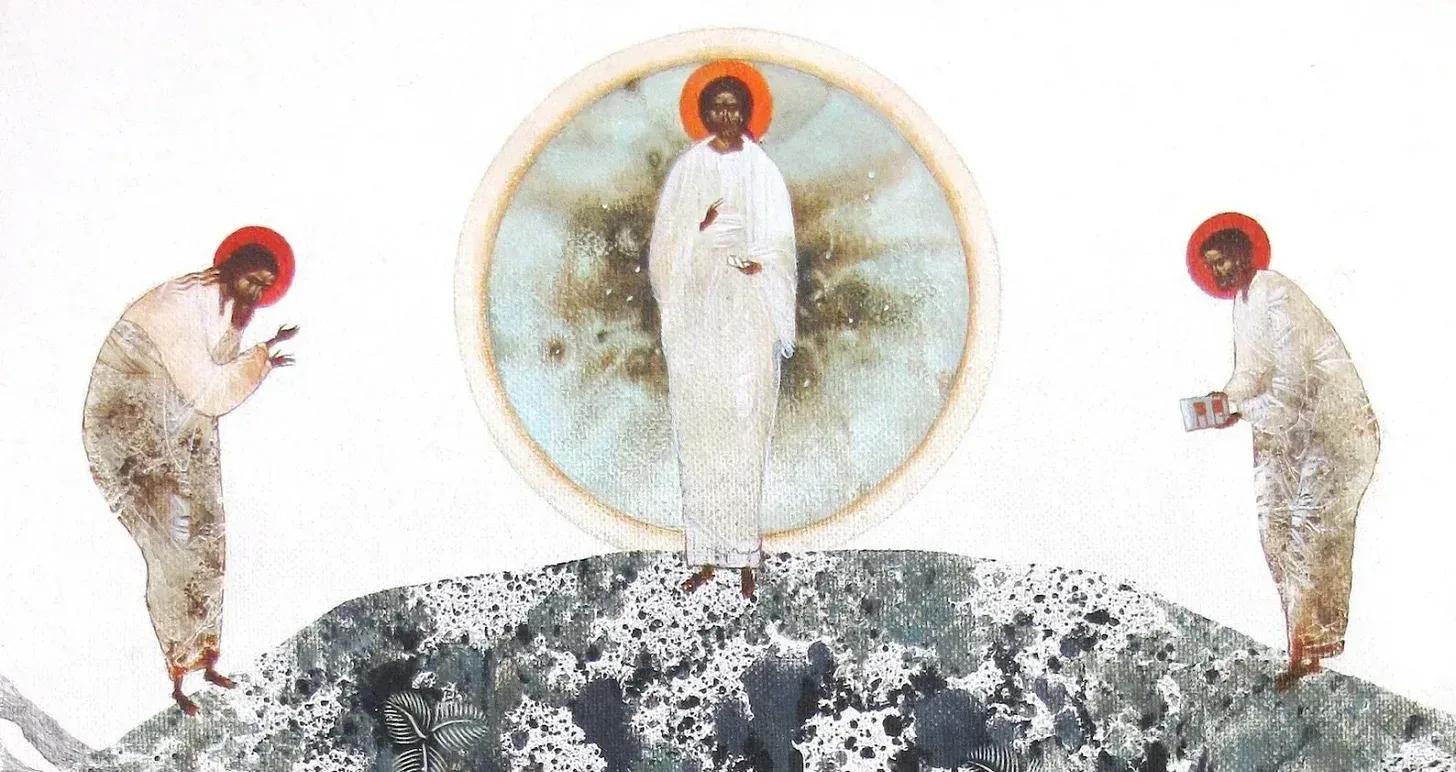

Jesus takes Peter, James, and John up a high mountain alone

and there he was transfigured.

Now,

many of the other feasts of the liturgical year

seem to carry a clearer story.

Christmas,

sure, I understand birthdays.

Annunciation;

well, I know what an announcement is,

so that makes sense.

But transfiguration

is not a word we use very often,

if ever.

Even if we break the word down to its parts—

“trans-” means to change,

“figure” means a visible representation or form,

“-ation” means the action or process of—

so the action or process of changing one’s visible form?

Yeah, still not much help.

Even the other texts don’t provide much insight.

Elijah is carried to heaven in a chariot of fire?

Really?

II Corinthians talks about the god of this age

vailing the gospel to those who are perishing.

Thanks, Paul.

What are we to make of all of this?

If we look closer,

both the story from II Kings

and the story from Mark

include disciples who don’t want things to change.

Elisha refuses to leave Elijah’s side,

despite the foretelling of his impending death,

until a mysterious light envelops Elijah

and he is gone.

Peter refuses to believe

that Jesus will die,

but Jesus begins to shine with a mysterious light,

flanked by Moses and Elijah,

and an overshadowing voice

calls Jesus “the Beloved”

and commands that they listen to him.

Jesus seemed to them

changed, somehow,

different in this new light.

For Peter, James, and John,

I wonder if this was the moment

when they understood what all the Law and the prophets

had been writing about.

I wonder if in a split second,

they knew in their bones

that they were looking at their God.

I wonder if that moment

had changed how they saw Jesus,

how they saw the rest of their lives.

Did it change how and what they dreamed

about the future?

Did it change how they saw everything they had been through

up to this point?

Was if transfiguration

not a changing of one’s visible form,

but a change in how the beholder

sees the visible form?

I know that Jennifer for me that day

was changed,

not in herself,

not in her form,

but in what she was to me.

For Elisha,

his beloved teacher did not die,

but was swallowed up in light,

carried out of his sight in the white-hot embrace

of God’s own Love.

For Peter, James, and John,

their beloved teacher

suddenly became more clearly visible to them

in a way that it changed how they saw everything else.

For them,

Jesus became the light by which

they could see everything else.

The Transfiguration is not a change of what we see;

the Transfiguration is a change in how we see.

Jesus has come to reconcile heaven and earth,

body and soul,

matter and spirit.

This is the “light of the knowledge

of the glory of God in Christ Jesus,”

the light by which we see everything rightly,

as it is,

for what it is.

Jesus is the light by which we come to understand

the law and the prophets,

heaven and earth,

body and soul,

matter and spirit,

sinners and saints,

are all reconciled to God

in Christ Jesus.

And if Jesus is the light

by which we can see

that God is reconciling all things to God’s self,

then we no longer have to worry about

what God might exclude.

Nor do we have to worry about

what God might include,

like suffering,

like the Cross,

like death and our sin.

Instead,

we are free to rest

in the overshadowing presence of God,

that great cloud of knowing

that surrounds us from without

and arises from within,

that assures us that we too are God’s Beloved,

and calls us to listen,

to await the transfiguring of this reality

until by God’s great Love and great Suffering

we arrive at the transformation

of this reality.

Amen.